- Home

- Bonnye Matthews

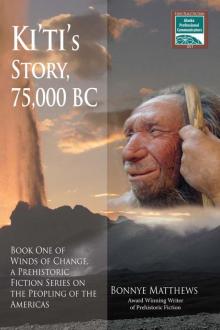

Ki'ti's Story, 75,000 BC Page 7

Ki'ti's Story, 75,000 BC Read online

Page 7

“Then we will help.” He assembled his hunters and told them what was happening. They went swiftly to their tools and gathered their cutting tools. They were ready.

Two of the hunters of the People left ahead of the rest.

Abiedelai-na asked Nanichak-na where they were going. “They are searching for more animals that we can use before they are too rotten.”

“Shall I send some of my hunters in a different direction?”

Nanichak-na considered the question. “No, Abiedelai-na, you should tell your hunters what is happening and watch to see what your hunters do.”

Abiedelai-na understood and did what Nanichak-na said. Abiedelai-na’s hunters looked at him. Suddenly, Arkan-na and Cue-na looked at each other. “We will go to search for carcasses also. We will go to the east since they go to the southwest.” Abiedelai-na translated.

Abiedelai-na and Nanichak-na both smiled broadly. The remaining Others followed the butchering hunters. It was good. Totamu looked through slitted eyes from her little alcove in the cave where she sat cross legged and wondered whether the good would last. She pulled her cover tightly around her shoulders as she shivered. Though the stories obligated them to care for those in need and wanderers, including Others, it did not remove in the least her inherent distrust of Others. She leaned over and spat upon the ground.

Chapter 2

The Winds of Change were blowing, but life was good, Shmyukuk thought. Wamumal, Mitrak, and Shmyukuk had padded the wall behind their sleeping mats and they were relaxing while their infants nursed. Shmyukuk was fascinated by Wamumal’s twins, Ekoy and Smig, whenever she had the chance to observe them closely. She hadn’t known that twins were a possibility in childbirth. Wamumal and Shmyukuk’s infants were the same age, a year; Mitrak’s infant, Ketra, was two years old. Trokug, Shmyukuk’s infant, still enjoyed playing with his mother’s black hair when he nursed. She shifted forward and began to delouse his hair. She noticed some attached eggs and tried to pull them off with her fingernails. She wiped the smear on her tunic.

Ey, a fifteen-year-old girl married to Arkan-na who was more than twice her age at thirty-three, was anxious. She was young but she had been joined with Arkan-na after his first wife died in childbirth. Ey had been horrified to have to join someone of his age with children some of whom were older than she, but soon got over it because of the gentleness and kindness of her husband. She had not known him until her group and his gathered to exchange mates. She had to leave her family and mother children older than she could have birthed. Her first child, Tita, was emaciated as badly as her mother, and Tita was about the size of a year-old child, not the two-year-old that she was. Ey, out of desperation, walked over to the nursing mothers and signed that she would like to sit with them.

Wamumal smiled broadly and signed for Ey to join them. Shmyukuk grabbed a skin and set it up for her to lean against between herself and Mitrak. They were appalled at the terrible thinness of Ey and Tita. Trokug, Shmyukuk’s one-year-old, had nursed to the point that he had fallen asleep. She laid him beside her and murmured. How, she wondered, do you communicate when you don’t speak the same language? She did, of course, speak the language of Ey, but she had been strictly forbidden to use it because it would slow down their learning the language they had to adopt. She pointed to her baby. They had already learned the names of each other but the names of the children remained to be learned. She said, “Trokug,” while she pointed to her infant. Ey said, “Trokug.” Ey then said, “Tita,” and pointed to her own infant.

To Wamumal’s amazement, Shmyukuk said, “Tita,” and pointed to herself saying her own name. Ey looked at her carefully and then handed Tita to Shmyukuk. Shmyukuk offered her breast to the tiny Tita. At first, Tita languished. Shmyukuk remained calm, knowing that the infant would either suckle or not and there was nothing she could do but offer to drip a bit of milk on the infant’s lips. Shmyukuk reached out and patted Ey’s hand. She was so pathetically thin. Shmyukuk had lived as a captive of the Minguat for a while. She knew these Others were a thin people, but the size of Ey made the normal Minguat look fat. Ey could do little but smile back. Finally, Ey placed her hand on her chest and patted Shmyukuk’s shoulder. She knew the word for grateful, but she had difficulty saying it. The infant began to suck. Slowly, tears fell from Ey’s eyes. Mitrak noticed and touched Ey’s shoulder, signifying compassion.

After a while, Shmyukuk placed her hand on Ey’s hand. She said, “I nurse Trokug.” She reinforced what she said with every hand signal she could think to use or create. “You bring Shmyukuk Tita. I nurse Trokug; you bring Shmyukuk Tita.” Finally, Ey understood that Shmyukuk was offering a wetnurse service. Ey lost more tears. She had all but given up on her daughter. Perhaps now she would live. Wamumal lost a few tears also. Her friend never ceased to amaze her. She would have been glad to help, but she had twins and that took all she had. While Ey rested, she thought of some in her group who had lost their children on the trek. She had been the only one to have kept her baby. At least ten or twelve babies had died. It had been a trek of many tears and there had been no time to mourn. She had all but given up on living until they had run into these People. Why had they been so kind? She could not understand. But she was grateful to the deepest center of herself. All of the babies drifted off to sleep. Barriers were breaking down. Mitrak told Shmyukuk that she would help feed Tita also. Little did Shmyukuk, Mitrak, or Wamumal understand what the other women had experienced. How it would have torn their bellies had they known.

Meanwhile, Totamu had asked the women who had agreed to make the booted garments. With the ash and the need to keep it out of the cave because it was already making people cough and it irritated skin, booted garments were critical to the health of all. She had shown the new women how to cut and construct the garments, but she was a person who checked to be sure that the garments were being made correctly. Where she saw error, she talked to the women and gently showed them how to fix the error. In their own language, two of the women spoke open resentment of Totamu’s apparent authority when all People were supposed to be equal. They also resented any authority from inferiors, which is how they viewed the People. Abiedelai-na overheard them and called them. He was acutely aware that Shmyukuk knew the language of the Minguat. He feared that she might hear slurs from his Minguat. He didn’t know whether any other People knew his language.

Aneal and Rayla got up and went to Abiedelai-na. “You have spoken our language!” he said accusingly.

“Yes,” Aneal said, “but it was between us.”

“That must stop now,” Abiedelai-na said in his language, using his right fist to strike his left palm after he mentally sorted out the right/left pattern. “This is the last time you will use our language while we are all together here.” Abiedelai-na was acutely aware how close his people were to death by starvation. He was not going to tolerate insurrection—not while they had an agreement that had been made that would save his people. “Further,” he said, “you were talking in an unkind manner about Totamu.”

Rayla frowned and pouted. “She’s got us making booted garments for children. Our children died on the trek. Why am I making something for their children? It’s not fair. Besides, since when do we take direction from inferiors?”

Abiedelai-na grabbed Rayla by the arm tight enough that it would later bruise. “You ungrateful girl! And you,” he said to Aneal, “these People did not take the life of your children. We would all be dead if we had remained in our homeland. We almost didn’t make it to safety. These People have brought us in and fed us and offered to take care of us through the season of cold days. We would have starved without them. To help keep this shelter free of ash, the garments are necessary. Have you not heard people coughing, as it is? Imagine ash in here. Your husbands are wearing booted garments now. Their legs will not be burning from the ash because they are protected. The cave is protected from ash because the garments are left at the cave entrance. And, you fools, some People understand our language. T

hey can hear you. You want us thrown out of here? You will work to the good of the group or I will personally throw you over my shoulder and carry you naked two days walk from here and leave you to fend for yourselves. Is that clear?”

The girls were shaken. Abiedelai-na was usually such a kind, gentle person for a Minguat. This seemed out of character to them. What he said stung. Neither had considered the need to keep ash out of the cave or that their husbands were benefiting from the work of the women who already lived in the cave. They had been self centered, selfish. Worse, they might be overheard and understood where their view of the People as inferiors was concerned. They would not wish to be responsible for the Minguat’s having to leave the cave in the cold.

“Finally,” Abiedelai-na said, “I do not want to hear our language from your mouths unless or until we separate at the end of the cold time. Remember that there are People who can understand our language. You just cannot use it. So if you want to talk to each other, you’d better get to learning their language.” He let go of Rayla’s arm and walked off. He no longer was Chief, but he knew that his authority was still there, just like their language—just in case. All knew that if they parted company with the People, Abiedelai-na would be Chief again, so his word was still law. He also knew and so did the girls that he would be good to his word if they continued with their language or their ungrateful attitude. He was always looking to the good of the group. Fortunately for the Minguat, most of the women heard what was said and by the time night fell, everyone in the cave would know even without a pronouncement. A new level of caution would overlay whatever they said or did.

Oho-na and Grypchon-na had gone out early to look for carcasses. Oho-na was becoming tired and thirsty. He had forgotten his water skin. He was slowing. Grypchon-na stopped and examined Oho-na. “You are thirsty?” he asked.

Oho-na nodded.

Grypchon-na pulled a water skin from his pouch. He held it out to Oho-na. Oho-na looked surprised. He wasn’t sure that if he’d have been among his own, the Minguat, whether anyone would have shared. They might have just made fun of him and let him go thirsty. He reached for the offered water pouch, lowering his head as far as possible. He drank the least he could to slake his thirst. Grypchon-na put the water away and pulled out two pieces of dried meat. He gave the thicker one to Oho-na. That wasn’t lost on Oho-na either. Oho-na had never met such selfless people. He was amazed and deeply grateful. Never again would he leave the cave without water and food. He wondered how he could have forgotten. He had much time to think and he was spending a lot of that time looking at the manner in which both groups had been operating. Oho-na looked up. He squinted, “There,” he stuttered as he pointed a little to the northeast in the monotonous monochrome landscape.

Both walked to the place. Sure enough, behind a little rise in the earth there was the carcass of another elephant. This time, it was the elephant with the large mastodon-like head roll and tiny ears. Grypchon-na grinned at Oho-na and then he kneeled and continued eating his dried meat. They had carried four long sticks and after they finished their dried meat, they put three of the sticks arranged in a tripod tied with a skin strip at the site so that it could be found more easily later. On the way back to the cave, they took the fourth stick to drag it through the ash to mark a path to the elephant. Their day had begun successfully.

Most of the men were on the meat butchering and preservation detail. Cave Sumbrel was busy and all the found carcasses had been butchered and moved to the cave. A few men had gathered sticks and were smoking meat already. There was little chatter and much work. Each knew that for the season-of-the-cold-days survival, they needed to gather as much meat as possible in the least amount of time. They were fortunate that insects were not present. It appeared that maggots would not be a problem.

Manak had been sent to the cave for additional cutting tools, and he returned with information that another elephant had been located. Manak, Slamika, Lamul, Gummo, and Ekwa were eager to go to the next carcass. Manak had reported that food was being prepared at the cave and would soon be ready, so the younger men had to return to the cave to eat and then they could go for the next carcass. Chamul-na had to smile. He knew that Manak was no slacker but he was genuinely pleased to see him take this critical food gathering so seriously. He was a grandson to approve.

Before they had reached the cave on their trek, Emaea’s People had gathered a huge supply of wood for cave use. It was stacked near the cave entrance and covered with skins as they had anticipated the ashfall. Since some of the new small booted garments had been completed, Minagle, Domur, Aryna, Meeka, and Liho had gone stick and wood gathering. They could easily see where Cave Sumbrel was by following the trail etched into the ash on the ground. They carried wood there as quickly and as much as possible. The girls tried very hard to shake off as much ash as possible from the wood before depositing it at the entrance to Cave Sumbrel for smoking. The girls were talking among themselves as well as they possibly could and the Minguat acquisition of the language of the People was being acquired expeditiously by the young. There was a lot of laughter. Minagle felt a return to earlier, happier times.

At the cave, Blanagah was still struggling. She could not imagine what to think of the disappearance of Reemast. She had even taken a light and gone to the depths of the cave seeking her absent husband. Finally, Mootmu-na, her father, told her that it was time for her to begin to realize that it would be unlikely that Reemast would return. He said that he suspected the young man was dead somewhere. Of course, he knew, but said it was clear that the situation was abnormal enough for his daughter to begin to give up hope. He also assured her that Reemast’s People did not seem overly concerned, which underscored the thought that the young man was probably dead. In some fundamental ways, Mootmu-na breathed a sigh of relief. The subject was closed. He no longer needed to pretend where Reemast was concerned. Blanagah had collapsed into his arms, but both knew that though she missed Reemast, she really didn’t know him well, and it would soon be time to get on with her life and find a new husband.

Wamumur called Ki’ti to him as soon as he had a break in his administrative duties. He noticed the young dog stuck to her like it had been tied. “Little Girl,” he began, “What is this dog doing out of its assigned place?” He tried to sound stern, but he was inwardly eager to know what her response would be.

Ki’ti lowered her head. Then she looked straight into Wamumur’s eyes and said, “Wise One, this little dog has asked to be my friend. I need a friend. I want the dog for a friend. If the dog makes trouble, I can get rid of him, but I ask from the innermost part of my belly to be allowed to keep the dog as my friend.”

Wamumur noticed that the dog sat right beside her. He looked at her, nothing else. He had seen no reason to deny her request except that never had such an idea of friendship with a dog been discussed, nor was it in the stories, but he wasn’t dealing with an ordinary child or ordinary circumstances and he knew it. The Winds of Change were blowing. “For right now, Little Girl, keep the dog. I will tell you tonight. I must think. Now we must work. Are you ready?”

“I will go to the privy and then I will be ready,” she said, doing her utmost to please the Wise One. Why, she wondered, did he call her Little Girl? Her name meant Falling Star. Ki’ti, Falling Star. Seenaha, Mootmu-na and Amey’s three-year-old, was a little girl, not she. She ran to the privy and the dog bolted for the place designated for dogs for the same purpose. She returned to Wamumur and they seated themselves in the same places as before but not before Emaea arrived with food and insisted they eat before starting another storytelling session. They did and Wamumur noticed that Ki’ti gave the dog a bit of her food. He frowned so she did not repeat the dog feeding. The dog snuggled against her side.

Ekuktu, still on cave assignment because Nanichak-na knew that he was trying to carve a louse comb, was working on the comb and finally took it to Totamu for her approval. Totamu smiled broadly at Ekuktu and took the comb into her hand. She looked

at it from every angle. Then she asked Ekuktu to kneel before her. She combed his hair with the comb. “It works!” she exclaimed when the teeth pulled out a louse and some eggs. “Will you make many of these?” she asked.

“How many?” he asked.

She raised one finger “for each woman in the size she needs for her and her husband and children and” she showed two fingers “extra of each size for each. Those with thicker hair will need a tiny bit more space. I think that the thicker hair might clog these teeth.”

“That’s a lot of combs!” he said, startled.

“It will keep you busy for a long time during the season of cold days, will it not?” Totamu said.

Ekuktu smiled at her. She knew he loved to carve. Totamu used the comb to get the rest of the lice and eggs from Ekuktu’s head.

“Now,” she said. “Tell your brother, Lamul, I want to see him after evening meal. Do not say why, but I will tell you. He is not pleased that you sit here and carve while he is out working. He thinks you play. He also has a head full of lice. I shall relieve his itching tonight so he may thank you.” A smile curved her lips.

Ekuktu lowered his head. “You are too kind,” he said.

Totamu kept the new comb knowing he had the old one and probably by now had the complete design in his mind web. “Nonsense,” she replied. Someday, she thought, he’d also realize how important keeping the peace was to survival. Tonight, Lamul would learn.

While the young girls headed back to the cave from their wood collecting, Domur asked Liho why she looked so different and where she got her yellow hair. Her use of language was halting but she managed to convey that she had been brought into the group one season of cold days ago. She lived among People who had yellow hair before that. Vanya, who was now sixteen, had asked his grandfather, then Chief Abiedelai, at a gathering of the groups to get him a blond headed wife. He thought the color was wonderful and it attracted him very much. His grandfather got a young girl, one not ready for joining, because Vanya wasn’t ready either. The girl was adopted by Arkan and Ey and would someday become Vanya’s wife. Liho was that girl.

The SealEaters, 20,000 BC

The SealEaters, 20,000 BC Tuksook's Story, 35,000 BC

Tuksook's Story, 35,000 BC Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC: Book Three of Winds of Change, a Prehistoric Fiction Series on the Peopling of the Americas (Winds of Change series 3)

Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC: Book Three of Winds of Change, a Prehistoric Fiction Series on the Peopling of the Americas (Winds of Change series 3) Ki'ti's Story, 75,000 BC

Ki'ti's Story, 75,000 BC Manak-na's Story, 75,000 BC

Manak-na's Story, 75,000 BC Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC

Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC