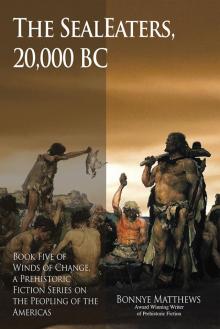

The SealEaters, 20,000 BC

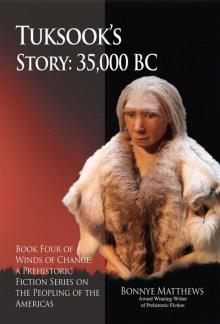

The SealEaters, 20,000 BC Tuksook's Story, 35,000 BC

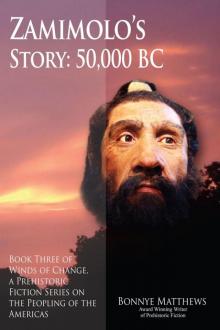

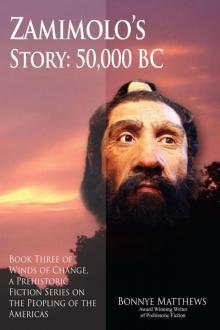

Tuksook's Story, 35,000 BC Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC: Book Three of Winds of Change, a Prehistoric Fiction Series on the Peopling of the Americas (Winds of Change series 3)

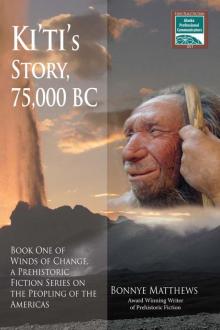

Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC: Book Three of Winds of Change, a Prehistoric Fiction Series on the Peopling of the Americas (Winds of Change series 3) Ki'ti's Story, 75,000 BC

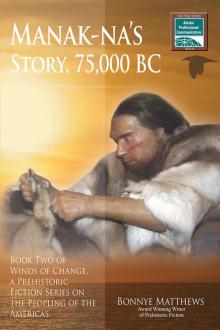

Ki'ti's Story, 75,000 BC Manak-na's Story, 75,000 BC

Manak-na's Story, 75,000 BC Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC

Zamimolo’s Story, 50,000 BC